What Happened To The Bodies At Hiroshima And Nagasaki

In 1945, the entire world watched the dropping of two atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. No one would forget.

Documenting the immediate aftermath was difficult. From the air, the view was obscured by smoke and fire. And on the ground? Things went from a perfectly ordinary — albeit war-torn — day to hell on earth. According to the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, it took a long time for the citizens of the two cities to even realize that the devastation had been carried on a single plane and dropped in a single attack. Death tolls have been impossible to determine for a number of reasons — and we'll talk about those reasons. For starters, though, let's talk about estimates: On the low end of things, the death toll was put at 70,000 for Hiroshima, and 40,000 for Nagasaki. At the high end, those numbers jump to 140,000 and 70,000, respectively. How could there be such a vast difference?

But first, the words of Emiko Okada, who was 8 when she survived the Hiroshima bombing. She explained the lasting impacts (via the BBC): "Every year there are a few times when the sky at sunset is deep red. It's so red that people's faces turn red. At those times, I can't help but think of the sunset on the day of the atomic bombing. For three days and three nights, the city was burning. I hate sunsets. Even now, sunsets still remind me of the burning city."

Death tolls are estimated because many bodies simply disappeared

There are a ton of numbers that are thrown out when it comes to the death tolls of the bombing of Hiroshima (pictured) and Nagasaki. The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists says the most oft-cited are between 110,000 and 210,000 for the two cities combined. Science says the Hiroshima bombing claimed between 90,000 and 120,000 lives, while Nagasaki suffered between 60,000 and 70,000 deaths.

In 1946, the Manhattan Project's Chief Medical Officer, Col. Stafford Warren, testified before Congress and explained that population records were iffy, no one knew who had died or simply fled in the chaos, and he summed up his investigation into the death toll like this: "I am embarrassed by the fact ... that we could not come back with any definitive figures that I would be able to say were more than a guess."

There was a larger problem, too, and it was explained by University of Pennsylvania sociologist Susan Lindee in her book "Suffering Made Real: American Science and the Survivors at Hiroshima." When it came time to count the dead, many were simply gone. Scores of people who were at the epicenter of the blast had been instantly turned to dust and ash, scattered on the wind. And others? They had headed to the rivers to try to stop the burning and the pain, and when they died there, their remains were carried out to sea.

Remains were cremated en masse

When the Manhattan Project's Chief Medical Officer, Col. Stafford Warren, gave his statement to the U.S. Congress in 1946, he said (via the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists) that there was only one concrete-ish number that he could attest to coming out of months of study. This, he said, was from Nagasaki (pictured): Their official records listed 40,000 bodies that had been cremated. Warren also said that this was much more precise than his own estimates: He suggested that another 20-30,000 bodies had been unrecovered for various reasons, with many cremated by the uncontrolled, raging fires that swept through the city in the aftermath of the blast, with others laying permanently buried by debris and destruction.

Eyewitnesses reported what seeing the mass, open-air cremations were like. Masako Wada was still a toddler when the bomb was dropped on Nagasaki, and recalled (via the Union of Concerned Scientists) that beside their home was a vacant lot used for mass cremations. "The corpses were cremated day and night. [My mother] became desensitized to the smell and the sheer number of people in front of her eyes. She said that everybody became numb to what was happening. What is human dignity? Should human beings be treated like that? We are not created to be burned like garbage."

Bones and ash littered the cremation sites for weeks after the burning stopped.

The remains of some were harvested and studied

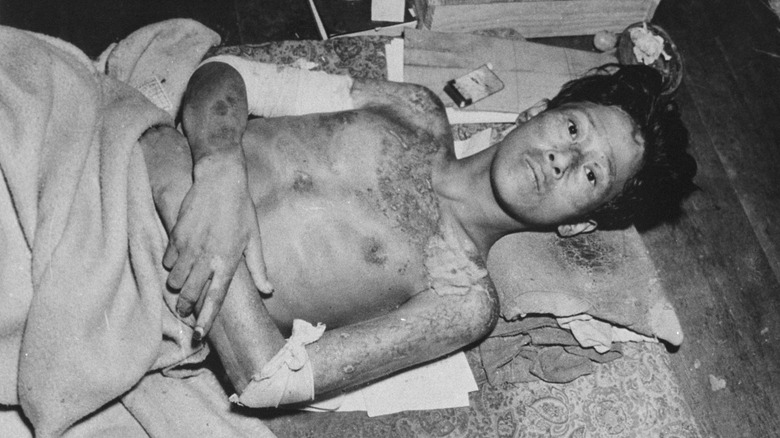

There were, of course, those who died instantly, and there were also those who languished in agony — however brief. That included an actress named Midori Naka, who has the dubious honor of being the first person to have her cause of death officially listed as radiation poisoning.

Naka — who was rescued from the remains of a destroyed building — survived the initial blast on August 6. By August 16, she was in the hospital with open sores, hair loss, and a rapidly dropping white blood count, and on August 24, she was dead. She quickly became the first of many radiation victims to be autopsied by the Japanese government in an attempt to learn more about radiation sickness and — hopefully — treat survivors, but here's where it gets even worse.

American medical professionals showed up at the end of September, and although Atlas Obscura says that the two nations initially worked together, all the material — including body parts and glass jars of "wet specimens" — was collected and sent back to the U.S. Names were changed to case numbers, organs were sliced and studied, identities disappeared when shipments were mislabeled and shuffled, and by the early 1950s, no one could even tell if the specimens — given designations like "A-14," and "158930-79" — had come from the same person. The American Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission was set up to keep studying what happened to survivors, and they continued to collect body parts for years.

The repatriation of remains took decades

The longer the American Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission worked, the worse and worse their reputation got. Atlas Obscura says that they were viewed as body-snatchers, with one man — Association of Atomic Victims founder Kiyoshi Kikkawa — calling the organization a "corpse-production facility." It wasn't until 1955 that the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology was opened, with the goal of consolidating the remains collected from the bomb victims. Record-keeping was iffy at best, and understandably, Japan was outraged and started calling for the remains to be returned.

That didn't happen until 1973. According to Susan M. Lindee of the University of Pennsylvania, it was in May of 1973 that Japan received seven massive crates filled with everything from photos and pieces of clothing to "wet tissue," or — in other words — organs, brains, and eyes preserved in formaldehyde. All told, there were around 23,000 such items returned, and Lindee reports that their ultimate treatment was surprising, to say the least.

"... the body parts appeared in Japan as both national property and crucial scientific data," Lindee writes. "Japanese pathologists were just as eager to study, slice, and display these pieces of human bodies as were their American counterparts, and in the Japanese journalistic treatment of these human remains ... they were referred to as 'data.'"

Tens of thousands rest in the Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound

The Hiroshima Peace Media Center is dedicated to preserving the memories of those who died in the bombing, of sharing information, and — hopefully — preventing such large-scale destruction from happening again.

They say that it was an unnamed man who — in 1946 — appealed to the city's mayor and asked for the construction of a space that would be used to honor those who died in the bombing. This became the Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound, a 16-ton dome of earth topped by a small pagoda. It stands on grounds that was once a Buddhist temple, which became one of many makeshift crematoriums in the aftermath of the bombing. Today, the ashes of 70,000 people rest within the mound's underground vault, along with the remains of others who were discovered in the months of cleanup that followed the detonation. That, says the Foreign Press Center Japan, includes the remains of 12 American soldiers who had been shot down over Japan, taken to Hiroshima for questioning, and were still there when the bomb dropped.

The City of Hiroshima says that all of those 70,000 people were unclaimed — most often because entire families perished. Others are unidentified, although DNA testing has led to the identification of some of the remains. Occasionally, more people are interred there: In 2004, 85 sets of remains were discovered on Ninoshima Island, and were given a final resting place in the Memorial Mound.

Families struggled to give their loved ones proper rites

Even as scores of people flocked to the cities to care for the dead and the dying, some families were left to their own devices when it came to seeing their loved ones die ... and then, giving them as proper a final rest as possible.

Yoshiro Yamawaki was 11 years old when he survived the atomic bombing of Nagasaki, and told Time: "One incident I will never forget is cremating my father." He and his brothers had found their father at a nearby factory, and — laying his nearly unrecognizable body down — they attempted a cremation. When they returned after the fire had gone out, he wasn't entirely cremated. In an attempt to give his spirit peace, the brothers decided to observe an old funeral tradition where bone was passed around with chopsticks: "As soon as our chopsticks touched the surface, however, the skull cracked open like plaster and his half cremated brain spilled out. My brothers and I screamed and ran away, leaving our father behind. We abandoned him, in the worst state possible."

Others had to carry the burden of knowing they had never given their loved ones any kind of peace. Kumiko Arakawa was 20 years old when she survived Nagasaki, losing one sister immediately, and three others — along with both of her parents — within days. She said she focused on gratitude, that her family's remains were given proper rites — unlike countless others, who are nothing more than a name etched on a gravestone.

This is how the shadows were really made

Some of the most infamous images of the aftermath of the dropping of the atomic bomb are the shadows etched on sidewalks and pavement around the cities. They're often said to be the shadows created as people were vaporized in their last moments on earth, but according to Dr. Michael Hartshorne of the National Museum of Nuclear Science and History, and the University of New Mexico School of Medicine (via LiveScience), they're not precisely what some might think.

The dark spots aren't precisely shadows cast, Hartshorne explains, but places that were protected by the heat and light of the intense blast because it was absorbed by something else: i.e., the people who had been standing there. It isn't the darkened "shadows" that were changed by the bomb — it was everything else around it, which was bleached in the light of the blast.

Before the bomb, the pavement, streets, and stairs all would have been the same color as the "shadows," and Hartshorne says that there were probably a lot more of the horrific images created in the aftermath of the blast. It would have happened as every body absorbed the energy of the blast and shielded whatever was behind them, but most were destroyed in the following shockwaves, fires, and heat blasts.

So. Many. Maggots.

The two atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki on Aug. 6 and 9, respectively, and average high temperatures were up around 90 degrees (via WeatherAtlas). High temperatures, open wounds, and scores of dead bodies meant there was another massive problem: maggots.

Reiko Hada was nine when she survived Nagasaki, and recalled (via the BBC) that she was on the opposite side of Mount Konpira as ground zero. She remembered the aftermath vividly: "It was summer. Because of the maggots and the terrible smell, the bodies had to be cremated immediately. They were piled up in the swimming pool at the college, and cremated with scrap wood."

It was a problem for the survivors, too: Masako Wada's mother volunteered with the injured, and her first assignment was to go from patient to patient and clean off the thumb-sized maggots (via the Union of Concerned Scientists). Shinichi Uramoto was part of a medical team sent to Hiroshima, and recalled the scene that unfolded as they got there (via Memories of Hiroshima and Nagasaki): "The severe burns were inflamed, purulent, and infested with maggots with flies swarming around. Their ears and noses in particular were stuffed with maggots." And Lee Jong-keun was 16 when he was caught in the Hiroshima blast, later telling the United Nations that as his mother plucked the maggots from his raw and oozing blisters, she told him, "I almost wish you were dead, so that you can at least rest in peace."

Dying for a drink of water

Accounts of the immediate aftermath of the dropping of the atomic bomb are as varied as the lives of those who tell them. Still, read enough of them, and something starts to stand out: The stories of people crying out for water, and dying after taking just a sip.

These are stories like Rikuko Sasaki's, who told of seeing people go to the rivers on Mount Hijiyama, holding out their hands and asking for water. Someone told her that if they were given any, they would die. Her neighbor, she said (via Memories of Hiroshima and Nagasaki), had water taken away, but died anyway. Inosuke Hayasaki spoke with Time, and told of walking away from Nagasaki and passing countless burn victims, all pleading for water. Knowing many had only a brief time left to live, he started bringing water to the victims from a nearby rice paddy. Among them was his friend, Yamada. "I placed my hand on his chest. His skin slid right off, exposing his flesh. I was mortified. 'Water ...' he murmured. I wrang the water over his mouth. Five minutes later, he was dead."

He lived with the burden of not knowing if — in his attempt at mercy — he had killed them. Did he? No, not necessarily. According to Dr. Hiroo Dohy of the Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital and Atomic Bomb Survivors Hospital (via Peace Seeds), drinking water could lead to more blood loss in severely wounded people. At that point, though, it was likely they were dying anyway.

A singular thing was responsible for most of the immediate deaths

In 1946, the Manhattan Engineer District compiled a report of all that was known about the aftermath of the atomic bomb (via the Atomic Archive). They determined that in the case of immediate deaths, only about 7% were caused by radiation. In fact, casualties from radiation were restricted to the immediate blast radius, while severe burns caused mass casualties as far away from the epicenter as 2.6 miles.

The report found that there was a shocking 93% mortality rate for those who were within 1,000 feet of the epicenter of the bomb, and that didn't drop below 50% until they started looking at casualties at around 5,000 feet. They also estimated that 60% of the deaths from Hiroshima were caused by burns, with 30% caused by falling debris. At Nagasaki, however, that jumped to a whopping 95% of deaths caused by burns.

They clarified further that there were two different kinds of burns: flash burns and flame burns. Flame burns were, as the name suggests, those caused by fire. Flash burns were much more devious, starting as reddened skin and quickly getting worse over the next few hours. The exposure of a flash burn is a few thousandths of a second, and although any kind of shielding would prevent them — even some kinds of clothing — these were also the burns that charred telephone poles, destroyed granite surfaces, and boiled roof tiles.

Those who survived paid the price for the rest of their lives

Various organizations have tracked the health and illnesses of survivors since the atomic bombs were dropped, and their findings have been dismal. Science reports high instances of things like cancer and leukemia, with survivors suffering from a myriad of other ailments and issues like anemia, tumors, thyroid issues, and miscarriages — along with struggles like survivors' guilt.

While those are generally well-known, there are other, less frequent but no less heartbreaking conditions that some survivors and their families have faced. Yasujiro Tanaka told Time that not only did he lose most of his hearing, but his skin continues to grow random scabs. His sister's kidney issues make dialysis a thrice-weekly process, and about ten years after the bombing, glass began growing out of his mother's skin where it had been embedded by the blast.

Fujio Torikoshi lives with a thick scar called a keloid on his neck, and he's not alone: Some survivors have developed so much scar tissue that they struggle to perform basic tasks. A study published in the journal Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences looked at suicide risk among survivors, and determined that mental health care was as important as physical care. Sachiko Matsuo lost her father: He died horribly in the aftermath of the bomb, and it was 50 years before he appeared to her in her dreams. "He was wearing a kimono and smiling, ever so slightly," she said (via Time). "Although we did not exchange words, I knew at that moment that he was safe in heaven."